Object Obituary: My Nikons

I wrote this for Wendy Ju’s magazine, Ambidextrous, back in 2008. Then some things happened in my life that interfered with my finishing the story for publication. Today I stumbled across the stack of drafts that had accumulated as I worked on a final edit and then stopped, four years and a few months ago. The drafts had floated forward through four or more laptops that I’ve had since then, allowing me to edit the work of a familiar stranger — a past version of myself — and to publish the essay here in the annals of Facebook for the first time anywhere. It still needs a patient, detached editor, and this isn’t a classy publication like Ambi, but you get the idea.

If any machine on Earth can steal a soul, the Nikon FM2 is that machine.

For more than half my life, I owned two FM2 bodies: hard-won rewards and professional upgrades from the chunky hobbyist Minoltas behind which I learned photojournalism.

Tucked into the wings of nightclub stages, we shot famous rockers and unknown cover bands. We were nearly trampled at the margins of pro football fields and college basketball courts. We met and memorialized minor politicians, women’s club awardees, Friday night high school athletes, and thousands of everyday people on the best and most terrible days of their lives.

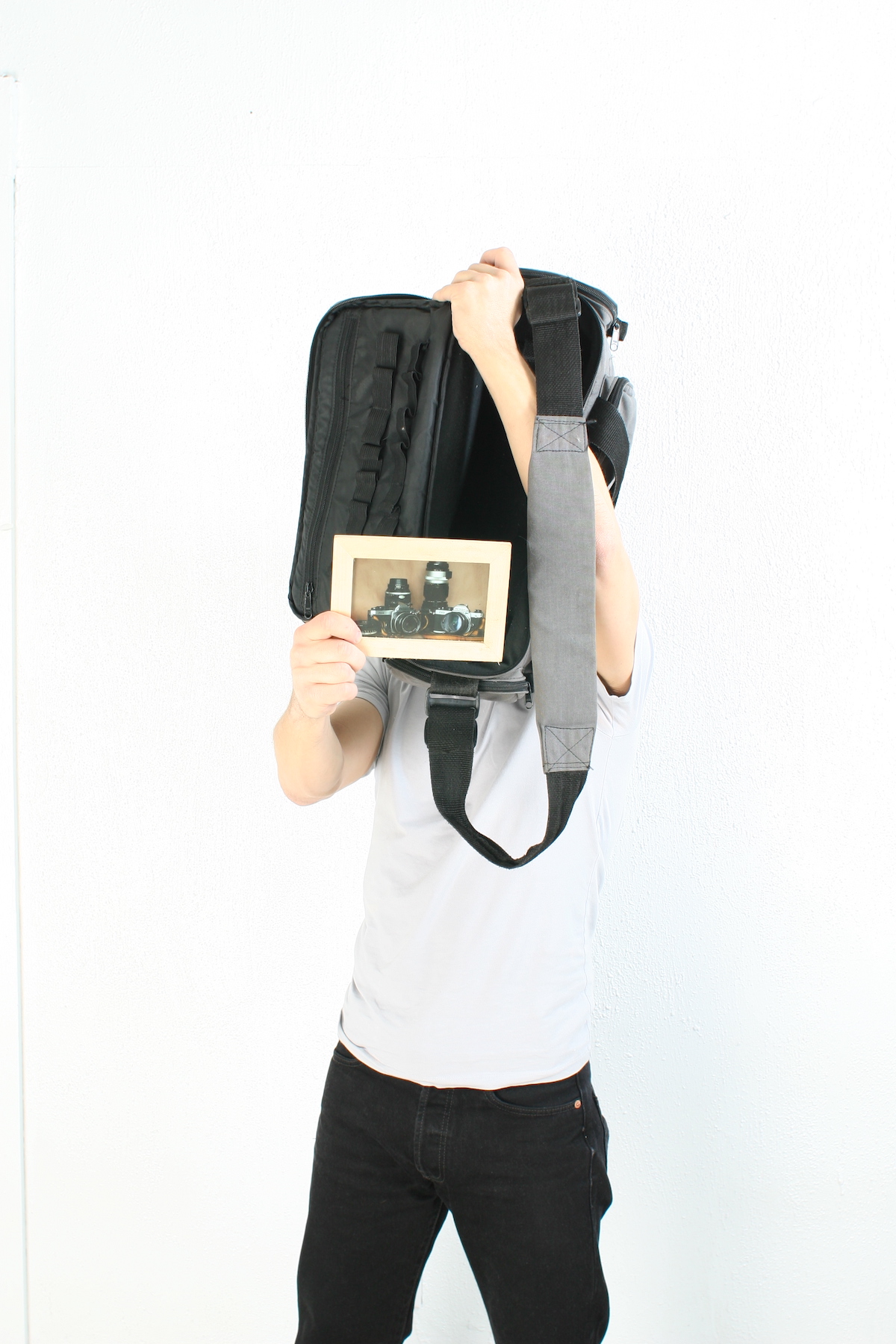

It was an unexpectedly intimate relationship. We were seldom more than a few feet apart. When not pressed to my face, the cameras hung from my shoulder or waited in the fitted, padded Kiwi bag that I carried to class, to work, cross-country and overseas, in case I needed to make a photo.

My friends went for the flashy Canon AE-1, laden with auto-exposure modes and blinking LEDs. I wanted performance. The all-manual FM2 has no computer, no image-stabilizing CCD. Used well, it barely exists: Subject, lens, mirror, me.

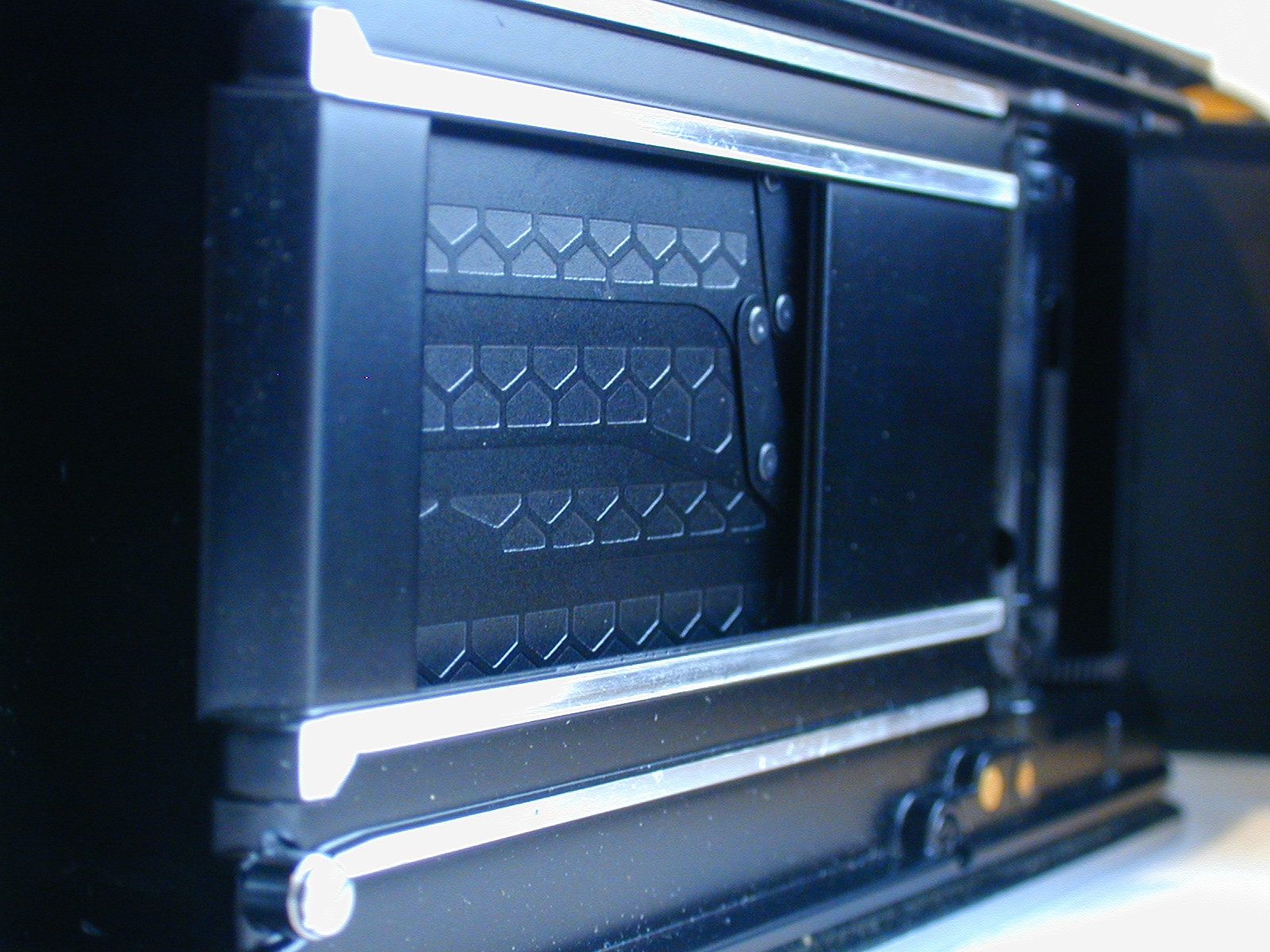

Its honeycomb-etched titanium shutter can flash-sync at 1/250 of a second and stop motion — any motion. More complex than a watch, the camera can bounce along in a bag or swing from a strap at temperatures from 20 below to 100 above, then deliver a precision image.

Over time, I acquired bright, manual-focus, fixed-length lenses, an original F body, some filters — nothing extravagant, everything purposeful. Some came from New York mail order houses, others from a used-camera shop in the shadow of Youngstown’s dead steel mills. I turned those lenses back on the rusted valley in which I found them. That was my world. My assignment was to catch it all on film for eternity.

An FM2 is professional gear, solid but not heavy. Lenses lock into the time-tested F-mount with a confident click. The 1/4000 sec. honeycombed titanium shutter is still considered a masterwork of mechanical engineering: smooth, reliable, and quiet.

The exposure controls, designed before “user experience” was an everyday phrase, are perfection. A photographer need never lower an FM2 from his eyes except to change the film. I learned to set the camera by touch, keeping subjects at ease by pretending to ignore it until the right moment: two clicks left on shutter speed; three right on the aperture; approximate focus; camera up, final focus, shutter, camera down. Beginners could fumble an FM2 as they would any other camera, but with practice one could /master/ the machine, turning the act of photography into a performance.

We’ve lost the rights and rites of mastery over our tools. Who or what is the photographer when software makes more decisions than the guy behind the viewfinder? Modern systems, designed for everyone, are designed for no-one. What is “expert mode” on a 12-point auto-focus lens?

One day I stopped taking photos with film, and for a while I didn’t take many photos at all. I don’t remember anything about the last photo I shot on film, but I cannot forget the day I realized that I had ignored the cameras for too long, placing them at risk of seizing up from disuse. We’re told not to love objects, but I loved those machines, their designers and builders, and my personal photographer-heroes who changed the world with images. I could not let them die sitting idle in a closet.

I prayed that the “lucky eBay-ers” who “won” them would appreciate them not just as “vintage collectibles,” not just as cameras, but as witnesses to all the lives whose reflections have streamed through them, and to all the souls they captured and made immortal. The kit was broken up for the first time in decades, sold piecemeal to individual buyers who wanted my gear as much as I wanted it to be appreciated: a professional photographer in Kansas, an art student in New York, a serious amateur in California, and another, amazingly, in Ohio where it all started for me.

My friends with good digital gear make beautiful photographs, and so do I. But whenever I see a beautiful digital photo, I wonder if it would have been even better with some film and an FM2.

-30-