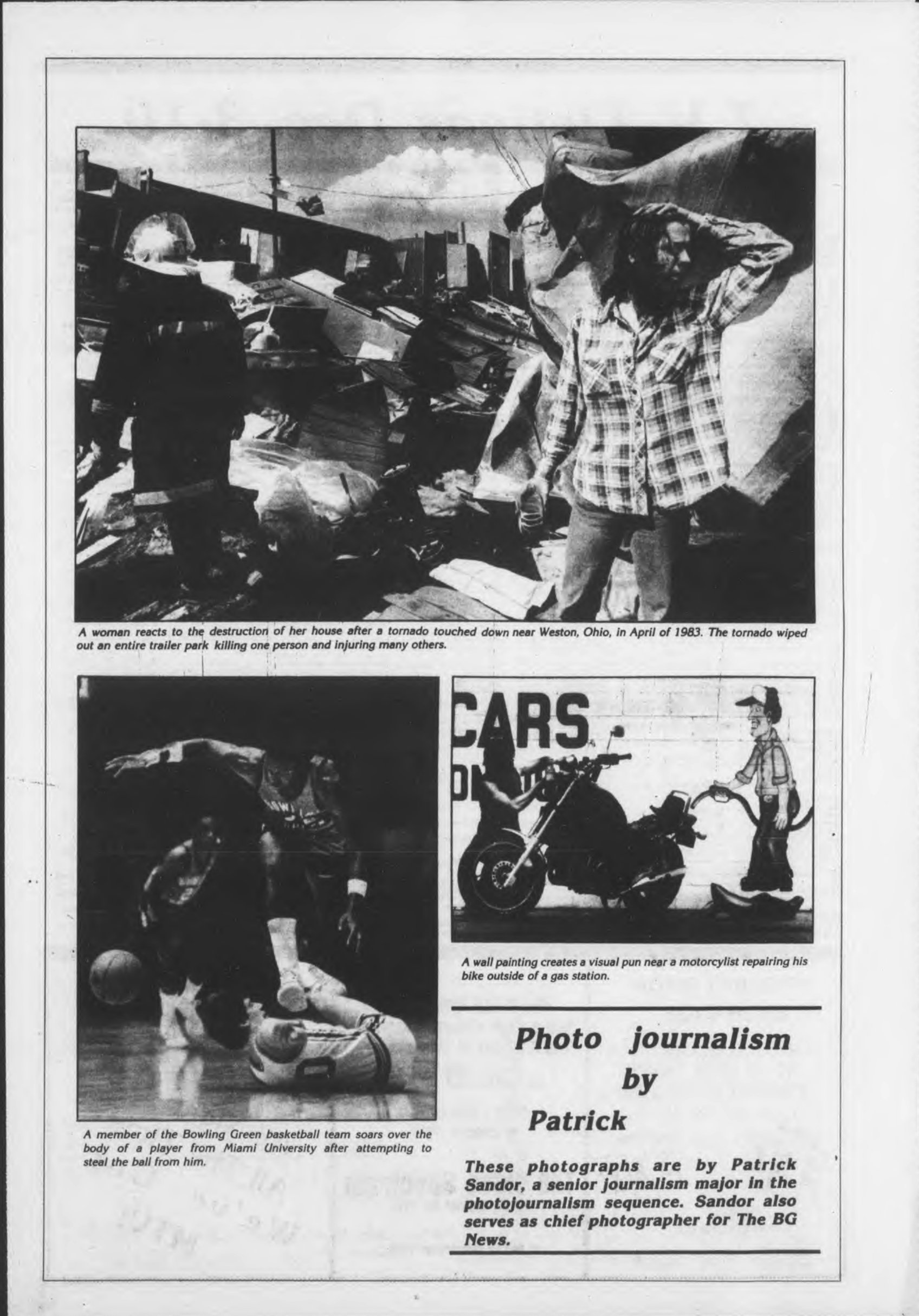

Patrick

Patrick was Chief Photographer at the student newspaper, The BG News, when I tumbled out of high school in tiny Niles, Ohio, and into college at Bowling Green State University in August, 1983.

I didn't choose Bowling Green. Bowling Green found me. I had been so determined to attend a renowned – and expensive – engineering school that I sent only a handful of half-hearted applications to other universities including Bowling Green, but hadn't seriously considered any of them. Then late in the last half of my high school senior year, a coldly-worded letter from the famous engineering school taught me a new phrase: "unmet need." The financial aid package came up desperately short. My family was poor. And the cash to fill the gap between financial aid and tuition for just one year was more than our combined net worth. I had no real backup plan.

A few days later, a student worker carrying two hall passes – one for them, one for me – pulled me out of math class to take an urgent call from my mother. I'd seen this happen to other kids. Most were gone for a few days, sometimes weeks. Some never returned. Those who did come back, came back different, quieter. "My grandpa died" or "my brother got sick" was all they'd say. Now it was my turn.

I scooped my books, pencils, pens, notepad into my backpack and followed the escort downstairs to the office. The secretary must have seen this script play out hundreds of times. She handed me the phone, stepped back from the counter and looked away. From the earpiece a full arm's length from my head, I heard my mother crying. I took a breath, moved the receiver to my ear, summoned my best grown-up voice to hide my fear of what was coming next, and blurted out two words:

"What's up?"

"I'm sorry"

"Mom?"

"I opened your mail"

"What?"

More sobbing.

"Mom, what?"

"Your mail. Bowling Green. I opened it. I'm sorry. I couldn't wait. Scholarship. Bowling Green is giving you a full scholarship. I'm sorry."

Now we were both crying.

Stunned and bewildered, I accepted the lifeline. My crisis was solved through the collective decision of a scholarship commitee whose very existence was unknown to me – a committee that discussed me, specifically, in a room somewhere on the campus of a school I had visited exactly once. This routine decision – one among hundreds made by those anonymous strangers around a table in a conference room – rerouted my life into an alternate reality only partly of my choosing – an alternate reality that had Patrick in it.

BG's photojournalism program was thriving then under Jim Gordon, a soft-spoken heavyweight in American news photography. Patrick, a senior, brilliant photographer, Gordon’s protege, was the program's star.

My achievements must have looked strong enough on paper to win that scholarship, but I knew the truth: I was unparented, half-grown, terminally introverted, scared, broke, undeniably single, and worst of all — I played tuba in the marching band.

Patrick, on the other hand, had a girlfriend — not just for funsies, but an actual relationship. They were probably having adult sex and everything. I’d barely dated, let alone had a casual anything with anyone.

My only firm memory of Patrick is from the day I met him. I interviewed for a photography job at the BG News early in my first semester. He was leaning against a desk in the newsroom: tall, handsome, confident, impressive haircut, wearing the Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark t-shirt that I’ve associated with him ever since. He said he was “back from New York,” so I assumed he had just seen the band in New York City where he lived, then returned to BG for the semester.

Cool. So cool. Of course I had never been to New York City.

There's a highway on-ramp about five miles from my Ohio hometown that drops onto Interstate 80 East. A mile from there on I80 East is a left exit signed: "New York City". It's 395 miles to New York from my hometown - about 6-1/2 hours driving time.

I drove past that sign hundreds of times in the years before college and always stayed to the right. People like me from places like Niles, Ohio don't drive to New York City. Those of us who had been to Cleveland knew something about the risks: numbered, one-way streets; graffiti; criminals; criminals painting graffiti along numbered, one-way streets. And New York City had another risk: Subways. In all my life leading up to the day I met Patrick and for a few years afterward, I had never been to a city that had a subway, let alone traveled in one. What if I got lost? What if criminals stole my wallet and I couldn't pay for the ride back to my hotel? It was all too scary and dangerous.

My people traveled in packs to scary places like New York City on safe, guided tours in air-conditioned motor coaches: "Breakfast, lunch, and lodging (double occupancy) included in the package price. Dinner on your own." I always wondered how people found dinner in an unfamiliar city like New York. My people traveled with foam coolers packed with ice, sandwiches and carrot sticks for car trips. On longer bus tours, we stuffed durable food like apples, Slim Jims, and candy bars into backpacks and purses - just in case.

All I knew about Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark – OMD as the insiders called them – was that they and their fans, Patrick included, were ultra-cool. Back in Niles, local FM stations sheltered us from modern music in a safe space dominated by blue-collar rockers like Bruce Springsteen, Bob Seger, Tom Petty, and The Eagles, with occasional psychedelic treats by Pink Floyd and Jethro Tull, plus Stairway to Heaven at least once a day. I was so far removed from Patrick’s kind of cool that even my profound appreciation of Pink Floyd wouldn’t have impressed him. The OMD shirt proved that Patrick’s radio could tune to frequencies that mine was unable to receive.

I'd been working as a photographer and writer for commercial newspapers all through high school, so I arrived for that student newspaper interview desperately overprepared. Patrick was nonchalant, but I heard about the laughter afterward. Apparently freshmen don't often show up at interviews for free college papers with resumes and portfolios.

I vaguely remember that he’d critique my work from time to time in an attempt to help improve my photography. We must have discussed and traded assignments. When I asked his permission to use the darkroom for a personal project, he laughed because it was such a trivial request and why would he care?

But I don’t recall a single casual chat about life or school or families or anything personal. He knew I wasn’t cool. I knew it too. With my tics, insecurities, small town naïveté and marching band tuba, I must have appeared as a boy to him as much as he seemed an adult to me.

There is a means of making a photo that elevates it from “snapshot” to “photograph” and then to indisputable “photojournalism”. I can’t explain how that happens, but I know it when I see it, and so do you. Technically it’s planning and timing — being in the right spot with the right lens, focus and exposure dialed in, firing the shutter a quarter-second ahead of the moment you’re trying to catch. But there are intangibles — presence, spirit, a connection to the subject that the photographer seizes and commits to film. Patrick could do that. His work drew respect, even reverence, from the student journalists around us, even if they couldn’t explain why – and from faculty as well. He was that good.

I found some pages of the BG News from that year. It was a newspaper produced by kids, except for Patrick’s photos. Framed by awkward headlines and cramped layouts — the work of students trying their best — are photographs made by a developing professional in command of his craft.

Patrick shared plenty of inside jokes with the editors — other seniors, his cohort, who respected his talent. Julie. Erin. Carolyn. (Why have their names and faces come with me across time while so much else was lost?). But he never divulged his inner thoughts in casual newsroom chatter like we kids did. They called him Partick after a typo wrecked his first name on a photo credit. When his last name was omitted entirely from the crooked, half-inch-high credit on his portfolio-destined, full-page, end-of-semester photo essay, he stayed in character even after processing the loss. His composure further lifted him, in my mind, into the stratum of the Adults.

While writing this, I looked up tour dates for Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark. They toured Europe in 1983, not the US. One year before, 1982, they staged 24 shows in 29 days across the US and Canada.

OMD performed in Detroit, Michigan on March 13, 1982. Detroit is 80 miles from Bowling Green, straight up Route 75. Patrick and his girlfriend could have driven to Detroit, seen the show, and been back home in BG, t-shirt in hand, by 2am.

Patrick’s OMD shirt wasn’t from a concert he had just seen in New York City before returning to Ohio. It came from his t-shirt drawer.

But a week before the Detroit show, OMD played in New York City. That’s how I choose to remember it: Patrick and his girlfriend, together at the The Savoy, March 5, 1982. They’re up front, stage right, about a third of the way in. The crowd is immersed in the moment, soaked in synth-pop, painted in stage light. His arms are around her. They're dancing - not wildly, but rocking together, eminently cool in that crowd of exceptionally cool people.

I learned after Patrick killed himself in 2001 at age 42 that he came to Bowling Green not from New York City, but from Tonawanda, New York — just outside Buffalo.

I know Tonawanda. It's a working class suburb of the factory town: Buffalo, New York, just like the place I'm from was a working class suburb of the factory town: Youngstown, Ohio.

It's 395 miles, a 6-1/2 hour drive, from Tonawanda to New York City, by an entirely different route, but precisely the same physical distance, travel time, and spiritual distance as from Niles, Ohio.

By spring of my junior year, a couple of years after Patrick graduated, Jim Gordon had become my mentor, too. He said he needed someone to shoot a photo for a story about New York Newsday. Was I interested?

This was no ordinary photo assignment. This was a photo credit in News Photographer: the official monthly magazine of the National Press Photographers Association, read cover-to-cover by every serious photojournalist in the country. Gordon edited and assembled News Photographer from a cozy, wood-paneled space in his home basement – shelves and tables stacked high with papers, photos, awards, camera gear, and the first FAX machine I ever saw up close. I'd been to the heart of News Photographer to help with the computers many times over the years, as other students had been to help Gordon with other tasks. But I never imagined my own work would be published from that venerated space.

Gordon – a news photographer, sage, professional observer of people – was our Obi Wan with waxed moustache and loupe. He pushed us to greatness, course-corrected projects gone wrong, opened doors for those who were paying attention. Looking back, I now believe the photo assignment was a calculated, insistent shove into the big world beyond my too-comfortable Ohio cocoon. New York had thousands of great photographers – and probably hundreds of NPPA members who could have made that photo. But Gordon sent me.

There was a catch: I'd have to drive myself to New York City and back over Spring Break (mileage paid).

A few weeks later on the cusp of the first of Spring, my classmates headed south to party in Fort Lauderdale and Daytona while I steered my candy-red, manual-transmission Ford Escort eastward, away from Bowling Green, hometown at my back, onto the Interstate 80 East ramp. A mile down the highway the Escort and I exited left under the "New York City" sign for the first time. I punched the gas with intent, launching car, self, and spirit on a 395-mile, 6-1/2 hour solo voyage into the stratum of the Adults to have a look around.

The obituary said that Patrick suffered from depression for many years - and that he died at his home in New York City. He really did reach the place I believed he'd always been. Of course he did. That kind of talent doesn't stay locked up in Bowling Green or Tonawanda.

I don't remember when or how it happened, but I'm an adult now, too. And when adult me thinks about Patrick – Patrick of the OMD shirt, Patrick the stoic, sophisticated, impossibly cool, depressed, brilliant photographer from New York City – I sort of get it: how hard life can be when your radio tunes to frequencies that most everyone else's can't receive. It must feel lonely in there.

I'll never be as cool as Patrick was, but sometime between the moment I exited left to New York City, and the moment I exited the my youth and became an adult, I began to understand how much we had in common all along.